Surgery

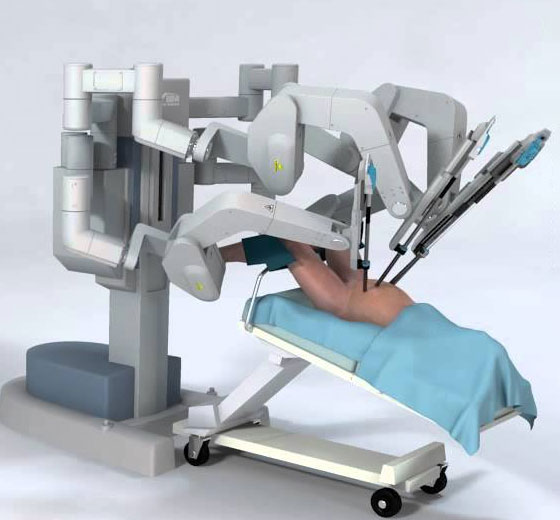

Robotic Radical Prostatectomy

Robotic Radical Prostatectomy is a minimally invasive robotic surgery in Kerala used for Prostate Cancer Treatment . During the procedure, a surgeon uses a robotic system to remove the entire prostate gland and surrounding tissue.

- Minimally invasive

- Robotic precision

- 3D visualization

- Reduced pain

- Low risk of recurrence

Surgery

Robotic Radical Nephrectomy

Robotic radical nephrectomy is a robotic surgical procedure that involves the removal of a kidney, along with the surrounding tissues and lymph nodes, using a robotic system.

- High precision

- Enhanced visualization

- Reduced complications

- Faster recovery

- Preservation of kidney function

Surgery

Robotic Partial Nephrectomy

Robotic Partial Nephrectomy is a minimally invasive robotic surgery used to remove a portion of the kidney affected by a tumor or other abnormal growth.

- Careful removal of kidney tumors

- Radical Cystectomy with Orthotopic Neobladder

- Faster recovery time than normal open surgery

- High success rate

Surgery

Robotic Pyeloplasty

Robotic pyeloplasty is a minimally invasive robotic surgery that is used to treat a condition called ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO).

- Robotic system

- Safe and effective treatment

- Improved outcomes

- Faster recovery

Surgery

Robotic Kidney Transplant

Robot Kidney Transplantation is a minimally invasive procedure that uses robotic assistance to complete kidney transplantation.

- Pain relief

- Reduced scarring

- Reduced risk of wound complications

- Shorter hospitalisation

Surgery

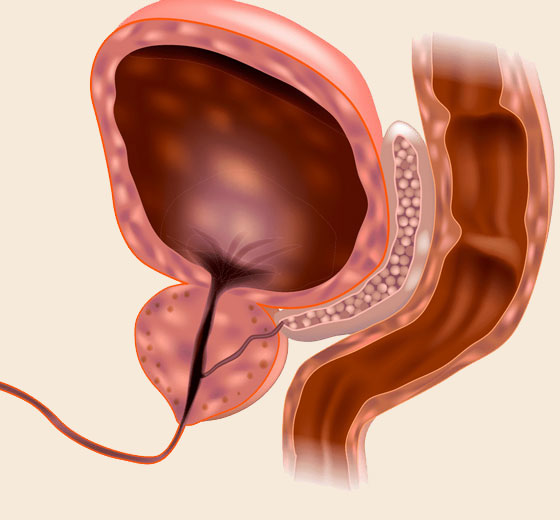

HoLEP (Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate)

HoLEP involves enucleation of the prostate rather than resection to achieve a near-total removal of the prostate gland.

- No risk of TURP syndrome

- Maximum gland removal

- Least recurrence risk

- Better Urinary flow

Surgery

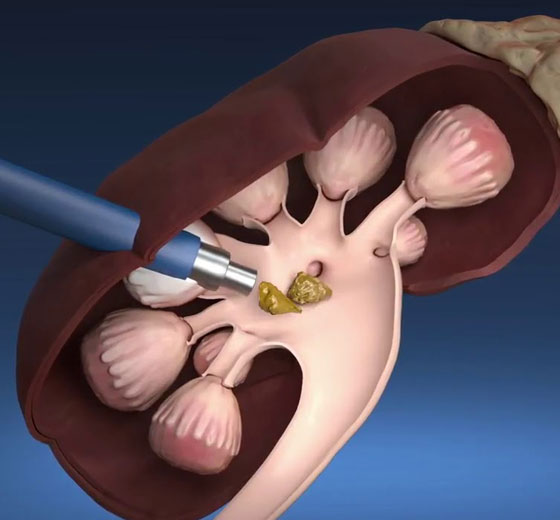

Retrograde Intrarenal (RIRS)

Retrograde Intra Renal Surgery (RIRS) is a minimally invasive surgical procedure used to treat kidney stones and other conditions affecting the urinary tract.

- Laser stone fragmentation

- Minimally invasive surgery

- Flexible ureteroscope

- Kidney stone removal

- Non-surgical treatment option

Surgery

Mini PCNL

Mini PCNL stands for Mini Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy, which is a minimally invasive surgical procedure used to remove kidney stones.

- Nephroscope-guided stone removal

- Small incision kidney stone surgery

- Modified PCNL procedure

- Precision stone removal surgery

Surgery

Urethroplasty

Urethroplasty is a surgical procedure used to treat urethral strictures, which are narrowings or blockages in the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the bladder out of the body.

- Urethral reconstruction

- Tissue grafting

- Penile surgery

- Urinary blockage treatment

Surgery

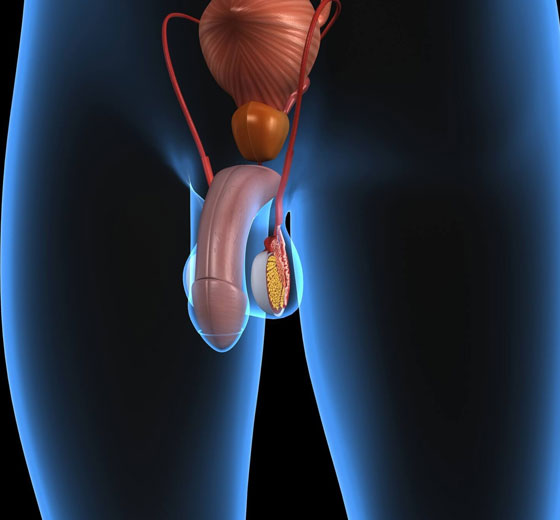

Penile Prosthesis Procedure

Penile Prosthesis Procedure is a surgical procedure used to treat erectile dysfunction (ED) in men who have not responded to other treatments such as medication or vacuum erection devices.

- Implantable Penile Device

- Erectile Dysfunction Treatment

- Surgical ED Treatment

- Prosthetic Penis Implant

Surgery

Microscopic Subinguinal Varicocelectomy

Microscopic sub-inguinal varicocelectomy is a surgical procedure that is used to treat varicoceles, which are enlarged veins in the scrotum that can cause pain, discomfort, and infertility.

- Fertility restoration

- Minimally invasive

- Microscopic approach

- Regional anesthesia

- Low recurrence rate

- Small incision

Treatment

UroLift

The UroLift system is a simple procedure that uses small implants to lift and hold enlarged prostate tissue, allowing for unobstructed urine flow. It does not involve cutting, heating, or removing any prostate tissue.

- One-Time Solution

- Faster Recovery

- Improved Urine Flow

- Rapid Relief

- Straightforward Procedure

FAQ

The procedure is generally carried out by a robot, which consists of small tools attached to a robotic arm that is controlled by a computer. One of the most widely used robotic systems in the world is the “Da Vinci system”.

- Prostate cancer

- Kidney cancer

- Kidney blockage

- Reconstruction of the kidney, ureter, and bladder

- BPH prostate removal

- High level of precision

- Flexibility

- Saves time

- Reduce manual labor

- Effective surgery in difficult-to-reach areas

- Increased recovery time

- Infection risk is low

- Scars are less